Top Quotes: “Born a Crime” — Trevor Noah

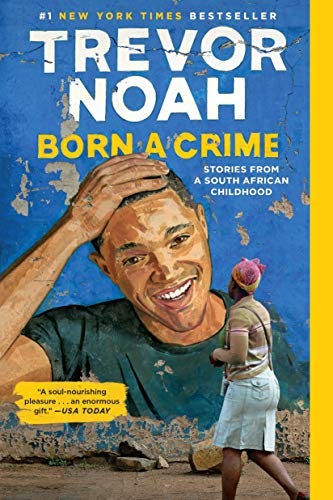

Background: The Daily Show host recounts his childhood growing up in poverty in South Africa and shares a ton of knowledge about apartheid. He has a wildly unique story as the son of a very intrepid and DGAF yet devoutly religious mother who grew up sleeping in cars and eating worms when they didn’t have money for food. I learned that I basically knew nothing about apartheid before and am so grateful to have improved my knowledge.

Apartheid

“The genius of apartheid was convincing people who were the overwhelming majority to turn on each other. You separate people into groups and make them hate one another so you can run them all. At the time, black South Africans outnumbered white South Americans nearly five to one, yet we were divided into different tribes with different languages. Long before apartheid existed, these tribal factions clashed and warred with one another. Then white rule used that animosity to divide and conquer. All nonwhites were systematically classified into various groups and subgroups. Then these groups were given differing levels of rights and privileges in order to keep them at odds.”

“The starkest of these divisions was between South Africa’s two dominant groups, the Zulu and the Xhosa. The Zulu man is known as the warrior and went to war with the white man. The Xhosa, on the other hand, pride themselves on being thinkers. Nelson Mandela was an Xhosa. Many Xhosa chiefs took a nimble approach, ‘These white people are here whether we like it or not. Let’s see what tools they possess that can be useful to us. Instead of being resistant to English, let’s learn English. We’ll understand what the white man is saying, and we can force him to negotiate with us.’ Neither group was particularly successful, and each blamed the other for problems neither had created. For decades those feelings were held in check by a common enemy. Then apartheid fell, Mandela walked free, and black South Africa went to war with itself.”

“The triumph of democracy over apartheid is sometimes called the Bloodless Revolution, because very little white blood was spilled. Black blood ran in the streets.”

“As the apartheid regime fell, we knew that the black man was now going to rule. But which black man? States of violence broke out between the Zulu Inkatha Freedom Party and the Xhosa-led African National Congress, as they jockeyed for power. Instead of uniting for peace, they turned on one another, committing acts of unbelievable savagery. Massive riots broke out. Thousands of people were killed. Necklacking was common — -that’s where people would hold someone down and put a rubber tire over his torso, pinning his arms. Then they’d douse him with petrol and set him on fire and burn him alive.”

“Under apartheid the government provided no public transit for blacks, but white people still needed us to show up to mop their floors and clean their bathrooms. Necessity being the mother of invention, black people created their own transit system, an informal network of bus routes, controlled by private associations operating entirely outside the law. It was basically organized crime. Different groups ran different routes, and they would fight over who controlled what. There was bribery, a great deal of violence, and a lot of protection money paid to avoid violence. The one thing you didn’t do was steal a route from a rival group. Drivers who stole routes would get killed. Being unregulated, minibuses were also very unreliable. When they came, they came. When they didn’t, they didn’t.”

“Apartheid was perfect racism. In 1652, when the Dutch East India Company established a trading colony later known as Cape Town, a rest stop for trips traveling between Europe and Asia, the Dutch colonists went to war with the natives to impose white rule, ultimately developing a set of laws to subjugate and enslave them. When the British took over the Cape Colony, the descendants of the original Dutch settlers trekked inland and developed their own language, culture, and customs, eventually becoming their own people, the Afrikaners — the white tribe of Africa. The British abolished slavery in name but kept in practice because a few lucky capitalists stumbled upon the richest gold and diamond reserve in the world, and an endless supply of expendable bodies was needed to go into the ground and get it all out.”

“As the British empire fell, the Afrikaner rose up to claim South Africa was his rightful inheritance. To maintain power in the face of the country’s rising and restless black majority, the government realized they needed a newer and more robust set of tools. They set up a formal commission to go out and study institutionalized racism around the world, reporting what worked, what didn’t. Then the government used that knowledge to build the most advanced system of racial oppression known to man. Apartheid was a police state, a system of surveillance and laws designed to keep black people under total control. In America you had the forced removal of the native onto reservations coupled with slavery followed by segregation. Imagine all three of those things happening to the same group of people at the same time. That was apartheid.”

“In any society built on institutionalized racism, race mixing doesn’t merely challenge the system as unjust; it reveals the system as unsustainable and incoherent. Race mixing proves that races can mix — and in a lot of cases, want to mix. Because a mixed person embodies that rebuke to the logic of the system, race-mixing becomes a crime worse than treason.”

“Unlike in America, where anyone with one drop of blood automatically became black, in South Africa mixed people came to be classified as their own separate group, neither black nor white but what we called ‘colored.’ Colored people, black people, white people, and Indian people were forced to register their race with the government. Based on these classifications, millions of people were uprooted and relocated. Indian areas were segregated from colored areas, which were segregated from black areas — -all of them segregated from white areas and separated from one another by buffer zones of empty land.”

“Laws were passed prohibiting sex between whites and all nonwhites. The government went to insane lengths to try to enforce these new laws. There were whole police squads whose only job was to go around peeking through windows — clearly an assignment only for the finest officers. And if an interracial couple got caught, the police would kick down the door, drag the people out, beat them, arrest them. At least that’s what they did to the black people. With the white person it was more like, ‘ Look, I’ll just say you were drunk, but don’t do it again, eh? Cheers.’ That’s how it was with a white man and a black woman. If a black man was caught having sex with a white woman, he’d be lucky if he wasn’t charged with rape.”

“The ultimate goal of apartheid was to make South Africa a white country, with every black person stripped of their citizenship and relocated to live in the homelands, semi-sovereign black territories that were in reality puppet states of the government. But this so-called white country could not function without black labor to produce its wealth, which meant black people had to be allowed to live near white areas in the townships, government-planned ghettos built to house black workers, like Soweto. The township was where you lived, but your status as a laborer was the only thing that permitted you to stay there. If your papers were revoked for any reason, you could be deported back to the homelands.”

“To leave the township for work in the city, or for any other reason, you had to carry a pass with your ID number; otherwise, you could be arrested. There was also a curfew: After a certain hour, blacks had to be back home in the township or risk arrest. My mother didn’t care. She was determined to never go home again. So she stayed in town, hiding and sleeping in public restrooms until she learned the rules of navigating the city from other black women who had contrived to live there: sex workers.”

“My mother never knew whom to trust, who might turn her into the police. Neighbors would report on one another. Black people worked for the government as well. As far as her white neighbors knew, my mom could have been a spy posing as a sex worker posing as a maid, sent to inform on whites who were breaking the law. That’s how a a police state works — everyone thinks everyone else is the police.”

“While most children are proof of their parents’ love, I was the proof of their criminality. The only time I could be with my father was indoors. If we left the house, he’d have to walk across the street from us. I couldn’t walk with my mother either; a light-skinned child with a black woman would raise too many questions.”

Soweto

“Soweto was designed to be bombed — that’s how forward-thinking the architects of apartheid were. The township had a population of nearly one million. There were only two roads in and out. That was so the military could lock us in, quell any rebellion. And if the monkeys ever went crazy and tried to break out of their cage, the air force could fly over and bomb the shit out of everyone.”

“In Soweto the police were an occupying army. They were militarized. They operated in teams known as flying squads, because they would swoop in out of nowhere, riding in tanks with enormous tires and slotted holes in the side of the vehicle to fire their guns out of. The township was in a constant state of insurrection; someone was always marching or protesting somewhere and had to be suppressed. Playing in my grandmother’s house, I’d hear gunshots, screams, tear gas being fired into crowds.”

“My grandmother refused to let me outside. My cousins, the neighborhood kids, they’d open the gate and head out and roam free and come out at dusk. I’d beg my grandmother to go outside and she’d say, ‘No, they’re going to take you.’ Children were taken. The wrong color kid in the wrong color area, and the government could come in, strip your parents of custody, haul you off to an orphanage.”

“I didn’t have any friends. I didn’t know any kids besides my cousins.”

“I come from a country where people are more likely to visit shamans than doctors of Western medicine. I come from a country where people have been arrested and tried for witchcraft. I’m not talking about the 1700s. I’m talking about five years ago. I remember a man being on trial for striking someone else with lightning. When someone gets killed by lightning, everyone knows it’s because somebody used Mother Nature to take out a hit. If you had a beef with the guy who got killed, someone will accuse you of murder and the police will come knocking.”

“I remember being told as a child, ‘If you don’t hit your woman, you don’t love her.’ This was the talk you’d hear from men in bars and on the streets.”

“For the million people who lived in Soweto, there were no stores, no bars, no restaurants. No paved roads, minimal electricity, inadequate sewerage. But when you put a million people together in one place, they find a way to make a life for themselves. A black-market economy rose up with every type of business being run out of someone’s house.”

“People built homes the way they bought eggs: a little at a time. Every family in the township was allotted a piece of land by the government. You’d first build a shanty of plywood and corrugated iron. Over time, you’d save up money and build a brick wall. Then you’d save up and build another wall. Then, years later, a third wall and eventually a fourth. Now you had a room, one room for everyone in your family to sleep, eat, do everything. Then you’d save up for a roof. Then windows. Then you’d plaster the thing. Then your daughter would start a family. There was nowhere for them to go, so they’d move in with you. You’d slowly build a proper room for them as well. Slowly, over generations, you’d keep trying to get to the point where you had a home.”

“My grandmother had a two-room house. Not a two-bedroom house. A two-room house. There was a bedroom, and then were was basically a living room/kitchen/everything else room. We all slept on the floor in one room, my mom and me, my aunt and my cousins, my uncle and my grandmother, and my great-grandmother. The adults each had their own mattresses, and there was one big one that we’d roll out into the middle, and the kids slept on that. We had two shanties in the backyard that my grandmother would rent out to migrants and seasonal workers. I never understood why my grandmother had a driveway. She didn’t have a car. She didn’t know how to drive. Yet she had a driveway. All of our neighbors had driveways, some with fancy, cast-iron gates. None of them had cars, either. There was no future in which most of these families would ever have cars. There was maybe one car for every thousand people, yet almost everyone had a driveway. It was almost like building the driveway was a way of willing the car to happen. The story of Soweto is the story of driveways. It’s a hopeful place.”

“Sadly, no matter how fancy you made your house, there was one thing you could never aspire to improve: your toilet. There was no indoor running water, just one communal outdoor tap and one outdoor toilet shared by six or seven houses. There had been a lid on the toilet at some point, but it had broken and disappeared. We couldn’t afford toilet paper, so on the wall next to the seat was a wire hanger with old newspaper on it for you to wipe.”

Language

“When I was growing up we used to get American TV shows dubbed into African languages. But if you wanted to watch them in English, the original American audio would be simulcast on the radio. You could mute your TV and listen to that.”

“A shared language says, ‘We’re the same,’ A language barrier says, ‘We’re different.’ The architects of apartheid understood this. Part of the effort to divide black people was to make sure we were separated not just physically but by language as well. In the Bantu schools, children were only taught in their home language. Zulu children learned Zulu. Because of this, we’d fall into the trap the government had set for us and fight among ourselves, believing that we were different.”

“My grandmother treated me like I was white. My grandfather did, too, only he was even more extreme. He called me ‘Mistah.’ In the car, he insisted on driving me in the backseat as if he were my chauffeur. There were so many perks to being ‘white’ in a black family, I can’t even front. I was having a great time. My own family basically did what the American justice system does: I was given more lenient treatment than the black kids. Misbehavior that my cousins would have been punished for, I was given a warning and let off. Growing up the way I did, I learned how easy it is for white people to get comfortable with a system that awards them all the perks.”

“I was famous in my neighborhood just because of the color of my skin. I was so unique people would give directions using me as a landmark. ‘The house on Makhalima Street. At the corner you’ll see a light-skinned boy. Take a right there.’ Whenever kids saw me on the street, they’d yell, ‘The white man!’ Some of them would run away. Others would call out to their parents to come look. Others would run up to me and try to touch me to see if I was real. What I didn’t understand at the time was that other kids genuinely had no clue what a white person was. Black kids in the township didn’t leave the township. Few people had TVs. They’d seen the white police roll through, but they’d never dealt with a white person face-to-face, ever.”

“I learned to use language to simulcast — give you the program in your own tongue. I’d get suspicious looks from people just walking down the street. ‘Where are you from?’ they’d ask. I’d reply in whatever language they’d addressed me in, using the same accent they had. It became a tool that served me my whole life. One day as a young man I was walking down the street, and a group of Zulu guys was walking behind me, closing in on me, and I could hear them talking to one another about how they were going to mug me. I couldn’t run, so I just spun around real quick and said in their language, ‘Yo guys, why don’t we just mug someone together? I’m ready. Let’s do it.’ They started laughing. ‘Oh sorry, dude. We thought you were something else. We were trying to steal from white people. Have a good day, man.’ They were ready to do me violent harm, until they felt we were part of the same tribe, and then we were cool. That, and so many other smaller incidents in my life, made me realize that language, even more than color defines who you are to people.”

Poverty

“The only way to make apartheid work was to cripple the black mind. The government built what became known as Bantu schools which taught no science, no history, no civics. They taught metrics and agriculture: how to count potatoes, how to pave roads, chop wood, till the soil.”

“The difference between British racism and Afrikaner racism was that at least the British gave natives something to aspire to. If they could learn to speak proper English and dress in proper clothes, if they could Anglicize and civilize themselves, one day they might be welcome in society. Afrikaner racism said, ‘Why give a book to monkey?’”

“Despite the fact that black people made up over 80% of South Africa’s population, the territory allocated for the homelands was about 11% of the country. There was no running water, no electricity. People lived in huts.”

“Where South Africa’s white countryside was lush and irrigated and green, the black lands were overpopulated and overgrazed, the soil depleted and eroding. Other than the menial wages sent home from the cities, families scraped by with little beyond subsistence-level farming.”

“For dinner, there might be one chicken to feed 14 children. My mother would have to fight with the bigger kids to get a handful of meat or a sip or the gravy or even a bone from which to suck out some marrow. And that’s when there was food for dinner at all. When there wasn’t, she’d steal food from the pigs. She’d steal food from the dogs. The farmers would put out scraps for the animals, and she’d jump for it. There were times when she literally ate dirt. She would go down to the river, take the clay from the riverbank, and mix it with the water to make a grayish kind of milk.”

“The curse of being black and poor follows you from generation to generation. My mother calls it ‘the black tax.’ Because the generations before you have been pillaged, rather than being free to use your skills and education to move forward, you lose everything just trying to bring everyone behind you back up to zero.”

“The end of apartheid was a gradual thing. Concessions were made here and there, some laws were repealed, others simply weren’t enforced.”

“If my mother and I weren’t at school or work or church, we were out exploring. She poured herself into me. She would find places for us to go where we didn’t have to spend money. We must have gone to every park in Johannesburg. We’d go for drive out in the country. My mom would find places with beautiful views for us to sit and have a picnic.”

“Food, or the access to food, was always the measure of how good or bad things were going in our lives.”

“When we were done with a chicken there was nothing left but the head. Sometimes the only meat we had was a packaged meat you could buy at the butcher called ‘sawdust’ that was literally the dust of the meat, the bits that fell off the cuts being packaged for the shop, the bits of fat and whatever was left. It was meant for dogs, but my mom bought it for us. There were many months when that was all we ate. Whenever times were really tough we’d fall back on dog bones. My mom would boil them for soup. We’d suck the marrow out of them. Sucking marrow out of bones is a skill poor people learn early.”

“As modestly as we lived at home, I never felt poor because our lives were so rich with experience. We were always out doing something, going somewhere. My mom used to take me on drives through fancy white neighborhoods. We’d go look at people’s houses, look at their mansions. We’d look at their walls, mostly, because that’s all we could see from the road. We’d look at a wall that ran from one end of the block to another and go, ‘Wow. That’s only one house. All of that is for one family.’ Sometimes we’d pull over and go up to the wall, and she’d put me up on her shoulders like I was a little periscope. I would look into the yards and describe everything I was seeing. ‘It’s a big white house! There’s a lemon tree! They have a swimming pool! And a tennis court!’ My mother took me places black people never went.”

“We tell people to follow their dreams, but you can only dream of what you can imagine, and, depending on where you come from, your imagination can be quite limited. The highest rung of what’s possible is far beyond the world you can see. My mother showed me what was possible. The thing that always amazed me about her life was that no one showed her. No one chose her. She did it on her own. She found her way through it through sheer force of will.”

“My mother started her little project, me, at a time when she could not have known that apartheid would end. There was no reason to think it would end; it had seen generations come and go. She was preparing me to live a life of freedom long before we knew freedom would exist. A hard life in the township or a trip to the colored orphanage were the far more likely options on the table. But we never lived that way. We only moved forward and we always moved fast, and by the time the law and everyone else came around we were already miles down the road, flying across the freeway in a bright-orange, piece-of-shit VW with the windows down.”

Mischief

“Chinese people were classified as black in South Africa. Unlike Indians, there weren’t enough Chinese people to warrant devising a whole separate classification. Apartheid didn’t know what to do with them, so the government said, ‘Eh, we’ll just call them black.’ Interestingly, at the same time, Japanese people were labeled as white. The reason for this was that the South African government wanted to establish good relations with the Japanese in order to import their fancy cars and electronics.”

“From an adult’s point of view, I was destructive and out of control, but as a child I didn’t think of it that way. I never wanted to destroy. I wanted to create. I wasn’t burning my eyebrows. I was creating fire. I wasn’t breaking overhead projectors. I was creating chaos, to see how people reacted. And I couldn’t help it. There’s a condition kids suffer from, a compulsive disorder that makes them do things they themselves don’t understand. You can tell a child, ‘Whatever you do, don’t draw on that wall.’ The child will look you dead in the eye and say, ‘Got it.’ Ten minutes later the child is drawing on the wall, looks at you, and has no idea why he drew on the wall.”

“My mom was smart and had a sharp tongue, but I was quicker in an argument. She’d get flustered because she couldn’t keep up. So she started writing me letters. That way she could make her points and there would be no verbal back and forth. If I had chores to do, I’d come home to find an envelope slipped under the door, like from a landlord: ‘Dear Trevor, There are certain things I expect from you as my child. You need to clean your room. You need to keep the house clean. You need to look after your school uniform. Please, my child, I ask you. Respect my rules so that I may also respect you. I ask you now, please go and do the dishes and do the weeds in the garden. Yours Sincerely, Mom.’ I would do my chores, and I had anything to say, I would write back. ‘To Whom It May Concern: Dear Mom, I have received your correspondence. I am delighted to say that I am ahead of schedule on the dishes and will continue to wash them for the next hour or so. Please note that the garden is wet and so I cannot do the weeds at this time, but please be assured that this task will be completed by the end of the weekend. Also, I completely agree with what you are saying in regards to my respect levels. Yours Sincerely, Trevor.’ If I found a punishment unfair, my mom would say, ‘If you want to reply, you have to write a letter.’”

“There was no punishment for me that day. My mom was too much in shock. There’s naughty, and then there’s burning down a white person’s house. She didn’t know what to do.”

“One of the biggest reasons why black people don’t like cats is, as we know in South Africa, only witches have cats, and all cats are witches. There was a famous incident during a soccer match a few years ago. A cat got into the stadium and out onto the pitch in the middle of the game. A security guard did what any sensible black person would do. He said to himself, ‘That cat is a witch.’ He caught the cat and — live on TV — he kicked it and stomped it and beat it to death. It was front-page news. White people lost their shit. The guard was arrested and put on trial and found guilty of animal abuse. What was ironic to me was that white people had spent years seeing video of black people being beaten to death by other white people, but this one video of a black man kicking a cat, that’s what sent them over the edge. In South Africa, black people have dogs.”

Dad

“My dad hates racism and homogeneity more anything. He never understood how white people could be racist in South Africa. ‘Africa is full of black people,’ he would say, ‘So why would you come all the way to Africa if you hate black people? If you hate black people so much, why did you move into their house?”

“Because racism never made sense to my father, he never subscribed to any of the rules of apartheid. In the early 80s, he opened one of the first integrated restaurants in Johannesburg. He applied for a special license that allowed businesses to serve both black and white patrons. These licenses existed because hotels and restaurants needed them to serve black travelers and diplomats from other countries; black South Africans with money in turn exploited that loophole to frequent those hotels and restaurants. My dad’s restaurant was an instant, booming success. Black people came because there were few upscale establishments where they could eat, and they wanted to come and sit in a nice restaurant and see what that was like. White people came because they wanted to see what it was like to sit with black people. The curiosity of being together overwhelmed the animosity keeping people apart. The place had a great vibe.”

Colored People

“To work the colonists’ farms, slaves were imported from different corners of the Dutch empire, from West Africa, Madagascar, and the West Indies. The slaves and the Khoisan intermarried, and the white colonists continued to dip in and take their liberties, and over time the Khoisan all but disappeared from South Africa. While most were killed off through disease, famine, and war, the rest of their bloodline was bred out of existence, mixed in with the descendants of whites and slaves to form an entirely new race of people: coloreds. Colored people are a hybrid, a complete mix. Some are light and some are dark. Some have Asian features, some have white features, some have black features. It’s not uncommon for a colored man and woman to have a child that looks nothing like either parent.”

“The curse that colored people carry is having no clearly defined heritage to go back to. Since their native mothers are gone, their strongest affinity has always been to their white fathers, the Afrikaners. Most colored people don’t speak African languages. They speak Afrikaners. Their religion, their institutions, all of the things that shaped their culture came from Afrikaners.”

“Every year under apartheid, some colored people would get promoted to white. People could submit applications to the government. Your hair might become straight enough, your skin might become light enough, your accent might become polished enough — -and you’d be reclassified as white. All you had to do was denounce your people, denounce your history, and leave your darker-skinned fiends and family behind.”

“The legal definition of a white person was completely arbitrary. That’s where the government came up with things like the pencil test. If you were applying to be white, the pencil went into your hair. If it fell out, you were white. If it stayed in, you were colored. Sometimes it came down to a lone clerk eyeballing your face and making a snap decision. He could tick whatever box made sense to him, thereby deciding where you could live, whom you could marry, what jobs and rights and privileges you were allowed.”

“Colored people didn’t just get promoted to white. Sometimes colored people became Indian. Sometimes Indian people became colored. Some blacks were promoted, and sometimes coloreds were demoted to black. And of course whites could be demoted to colored as well. That was key. Those mixed bloodlines were always lurking, waiting to peek out, and fear of losing their status kept white people in line. If two white parents had a child and the government decided the child was too dark, even if both parents provided documentation proving they were white, the child could be classified as colored, and the family had to make a decision. Do they give up their white status to go and live as colored people in a colored area? Or would they split up, the mother taking the colored child to live in the ghetto while the father stayed white to make a living to support them?”

Enterprise

“Petrol for the car, like food, was an expense we could not avoid, but my mom could get more mileage out of a tank of petrol than any human who has ever been on a road in the history of automobiles. Every time she stopped in traffic, she’d turn off the car. That stop-start tech they use in hybrids now? That was my mom. She was the master of coasting. She knew every downhill between work and school, between school and home. She could time the traffic lights so we could coast through intersections without using the brakes or losing momentum.”

“I was the fastest kid in school and the second we were dismissed from assembly, I would run like a bat out of hell to the snack shop so I could be the first one there. I became notorious for being that guy, so much so that people started approaching me during assembly. They’d say, ‘Hey, I’ve got ten rand. If you buy my food for me, I’ll give you two.’ I started telling everyone at assembly, ‘Place your orders. Give me a percentage of what you’re going to spend, and I”ll buy your food for you.’ I was an overnight success. I had all these rich, fat white kids who were like, ‘This is fantastic! My parents spoil me, I’ve got money, and now I’ve got a way I can get food without having to work for it.’ I would make so much that I could buy my lunch using other kids’ money and keep the lunch money my mom gave me for pocket cash. Then I could afford to catch a bus home instead of walking or save up to buy whatever.”

“I’d found my niche. Since I belonged to no group, I learned to move seamlessly between groups. I learned how to blend. I could play sports with the jocks. I could talk computers with the nerds. I could jump in the circle and dance with the township kids. I popped around to everyone, working, chatting, telling jokes, making deliveries. I was like a weed dealer, but of food. The weed guy is always welcome at the party. He’s not a part of the circle, but he’s invited into the circle temporarily because of what he can offer. That’s who I was. Always an outsider. As an outsider, you can retreat into a shell, be anonymous, be invisible. Or you can go the other way. You protect yourself by opening up. You don’t ask to be accepted for everything you are, just the one part of yourself that you’re willing to share. For me it was humor. I learned that even though I didn’t belong to one group, I could be a part of any group that was laughing. I never overstayed my welcome. I wasn’t popular, but I wasn’t an outcast. I was everywhere with everybody, and at the same time I was all by myself.”

“I’d hear people laughing and playing behind a brick wall and get off my bike and creep up and peek over someone’s swimming pool. I was like a Peeping Tom, but for friendship.”

“Many domestic workers in South Africa, when they get pregnant they get fired. Or if they’re lucky, the family they work for lets them stay on and they can have the baby, but then the baby goes to live with relatives in the homelands. Then the black mother raises the white children, seeing her own child only once a year at the holidays.”

“Walking around was pretty much all I did back then. I couldn’t afford to do anything else, and I couldn’t afford to get around any other way. If you liked walking, you were my friend. My friend Teddy and I would walk from my house down to the city center, which was like a three-hour hike, just to hang out and then we’d walk all the way back.”

“Every day in South Africa you see people completely lost, trying to have conversations and having no idea what the other person is saying. The more common your tongue, the less likely you are to learn others. The more fringe, the more likely you are to pick up two or three. In the cities most people speak at least some English and usually a bit of Afrikaans, enough to get around. You’ll be at a party with a dozen people where bits of conversation are flying by in two or three different languages. You’ll miss part of it, someone might translate on the fly to give you the gist, you pick up the rest from the context, and you just figure it out.”

“The government would find some patch of arid, dusty, useless land, and dig row after row of holes in the ground — -a thousand latrines to serve 4,000 families. Then they’d forcibly remove people from illegally occupying some white area and drop them off in the middle of nowhere with some pallets of plywood and corrugated iron. We’d watch it on the news. It was like some heartless, survival-based reality show, only nobody won any money.”

“In Germany, no child finishes high school without learning about the Holocaust — the how and the way and the gravity of it, what it means. British schools teach colonialism the same way, to an extent. Their children are taught the history of the Empire with a kind of disclaimer hanging over the whole thing. ‘Well, that was shameful, wasn’t it?’”

“In South Africa, the atrocities of apartheid are taught the way history is taught in America. ‘There was slavery and there was Jim Crow and there was MLK and now it’s done.’ For us: ‘Apartheid was bad. Mandela was freed. Let’s move on.’ Facts, but not many, and never the emotional or moral dimension. It was as if the teachers, many of whom were white, had been given a mandate. ‘Whatever you do, don’t make the kids angry.’”

“Life was good, and none of it would have happened without my white friend Andrew. Without him, I would have never mastered the world of music piracy and lived a life of endless McDonalds. What he did showed me how important it is to empower the dispossessed and the disenfranchised in the wake of oppression. Andrew’s family had access to education, resources, computers. My family had been denied the things his family had taken for granted. I had a natural talent for selling to people, but without knowledge or resources, where was that going to get me? People always lecture the poor: ‘Take responsibility for yourself! Make something of yourself!’ But with what raw materials are the poor to make something of themselves? People love to say, ‘Give a man a fish and he’ll eat for a day. Teach him to fish, and he’ll eat for a lifetime.’ What they don’t say is, ‘And it would be nice if you gave him a fishing rod.’ That’s the part of the analogy that’s missing. Working with Andrew was the first time in my life I realized you need someone from the privileged world to come to you and say, ‘Okay, here’s what you need, and here’s how it works.’ Talent would have gotten me nowhere without Andrew giving me the CD writer. People say, ‘Oh, that’s a handout.’ No. I still have to work to profit by it. But I don’t stand a chance without it.”

“Street parties are the best part of the Alexandra township. You get a tent, put it up in the middle of the road, take over the street, and you’ve got a party. There’s no formal invites or guest list. You just tell a few people, word of mouth travels, and a crowd appears. If you own a tent, you have the right to throw a party in your street. Cars creep up to the intersection and the driver will see the party blocking the way and shrug and make a U-turn. Nobody gets upset. The only rule is that if you throw a party in front of somebody’s house, they get to come and share your alcohol. The parties don’t end until someone gets shot or a bottle gets broken on someone’s face.”

“The thing Africans don’t have that Jewish people have is documentation. The Nazis kept meticulous records, took pictures, made films. When you read through the history of atrocities against Africans, there are no numbers, only guesses. It’s harder to be horrified by a guess. When Portugal and Belgium were plundering Angola and the Congo, they weren’t counting the black people they slaughtered. How many black people died harvesting rubber in the Congo? In the gold and diamond mines of the Transvaal?”

“Cheese was always the thing because it was so expensive. Forget the gold standard — the hood operated on the cheese standard. Cheese on anything was money. If you got a cheeseburger, that meant you had more money than a guy who just got a hamburger. If you had a bit of money, people would say, ‘Oh, you’re a cheese boy.’ In essence: You’re not really hood because your family has enough money to buy cheese.”

“The unemployment rate, technically speaking, was ‘lower’ during apartheid, which makes sense. There was slavery — that’s how everyone was employed. When democracy came, everyone had to be paid a minimum wage. The cost of labor went up, and suddenly millions of people were out of work. The unemployment rate for young black men post-apartheid shot up, sometimes as high as 50%. What happens to a lot of guys is they finish high school and they can’t afford university, and even little retail jobs can be hard to come by when you’re from the hood and you look and talk a certain way. So, for many young black men in South Africa’s townships, freedom looks like this: Every morning they wake up, maybe their parents go to work or maybe not. Then they go outside and chill on the corner the whole day, talking shit. They’re free, they’ve been taught how to fish, but no one will give them a fishing rod.”

“In the hood, gangsters were your friends and neighbors. You knew them. You talked to them on the corner, saw them at parties. You knew them from before they became gangsters. It was, ‘Oh, little Jimmy’s selling crack now.’ The weird thing about these gangsters was that they were all, at a glance, identical. They drove the same red sports car. They dated the same beautiful 18-year-old girls. It was strange. It was like they didn’t have personalities; they shared a personality. They’d each studied how to be that gangster.”

“In the hood, even if you’re not a hardcore criminal, crime is in your life in some way or another. It’s everyone from the mom buying some food that fell off the back of a truck to feed her family, all the way up to gangs selling military-grade weapons. The hood made me realize that crime succeeds because crime does the one that government doesn’t do: crime cares. Crime is grassroots. Crime looks for the young kids who need support and a lifting hand. Crime offers internships and summer programs and opportunities for advancement. Crime gets involved in the community. Crime doesn’t discriminate.”

“He said, ‘When white people lose stuff they have insurance policies that pay them cash for what they’ve lost, so it’s like they’ve lost nothing.’ ‘Oh okay,’ I said, ‘Sounds nice.’ And that was as far as we ever thought about it: When white people lose stuff they get money, just another nice perk of being white.”

“It’s easy to be judgmental about crime when you live in a world wealthy enough to be removed from it. But the hood taught me that everyone has different notions of right and wrong, different definitions of what constitutes crime, and what level of crime they’re willing to participate in. If a crackhead comes through and he’s got a crate of Corn Flake boxes he’s stolen out of the back of a supermarket, the poor mom is thinking, ‘My family needs food and this guy has Corn Flakes,’ and she buys the Corn Flakes.”

“The hood is a low-stress, comfortable life. All your mental energy goes into getting by, so you don’t have to ask yourself any of the big questions. Who am I? Who am I supposed to be? Am I doing enough? In the hood you can be a 40-year-old man living in your mom’s house asking people for money and it’s not looked down on. You never feel like a failure in the hood, because someone’s always worse off than you, and you don’t feel like you need to do more, because the biggest success isn’t that much higher than you.”

“In two years of hustling, I never once thought of it as a crime. I honestly didn’t think it was bad. It’s just stuff people found. White people have insurance. Whatever rationalization was handy. In society, we do horrible things to one another because we don’t see the person it affects. We don’t see their face. We don’t see them as people. Which was the whole reason the hood was built in the first place, to keep the victims of apartheid out of sight and out of mind. Because if white people ever saw black people as human, they would see that slavery is unconscionable. We live in a world where we don’t see the ramifications of what we do to others, because we don’t live with them.”

“In the township, getting arrested was a fact of life. It was so common that out on the corner we had a sign for, a shorthand, clapping your wrists together like you were being put in handcuffs.”

Mother

“My mother said, ‘The reason I ride you so hard is because I love you. If I don’t punish you, the world will punish you even worse. The world doesn’t love you. If the police get you, the police won’t love you. When I beat you, I’m trying to save you. When they beat you, they’re trying to killl you.’”

“The whole tradition of women bowing to the men, my mom found that absurd. But she didn’t refuse to do it. She made a mockery of it. The other women would bow before men with this little curtsy. My mom would go down and cower, groveling in the dirt like she was worshiping a deity, and she’d stay down there long enough to make everyone uncomfortable. To my stepdad, it looked like his wife didn’t respect him. Every other man had some docile girl.”

“We lived in the auto garage after my mom gave up everything for my stepdad. Gray concrete floors stained with oil and grease, old junk cars and car parts everywhere. Abel and my mom slept with my younger brother Andrew in the office on a thin mattress they’d roll out on the floor. I slept in the cars. I got really good at sleeping in cars. I know all the best cars to sleep in. The worst were the cheap ones, the VWs, low-end Japanese sedans. The seats barely reclined, no headrests, cheap fake leather seats. When I got a Buick, it was a good night.”

“We were so broke that for weeks we ate nothing but bowls of a kind of wild spinach, cooked with caterpillars. Mopane worms, they’re called. Mopane worms are literally the cheapest thing that only the poorest of poor people eat. I grew up poor, but there’s poor and then there’s, ‘Wait, I’m eating worms.’ They’re spiny, brightly colored caterpillars the size of your finger. They have black spines that prick the roof of your mouth as you’re eating them. When you bite into one, it’s not uncommon for its yellow-green excrement to squirt into your mouth.”